Meltwater Peregrinations II

In order to continue with this narrative arc, I need to set the context for what follows, and return briefly to November 2017, one month after I published Part I of Meltwater Peregrinations.

Introduction

In that month the first edition of Way Too Concrete – Footnotes on the Spatial took place, an event organised by myself, Sandra Bartoli, and Fiona Shipwright. In our own blurb, Way Too Concrete is “a semi-regular series of screenings, lectures and discussions exploring aspects of spatial production, representation and perception – finding comedy in the academic, and the profound in the banal.”

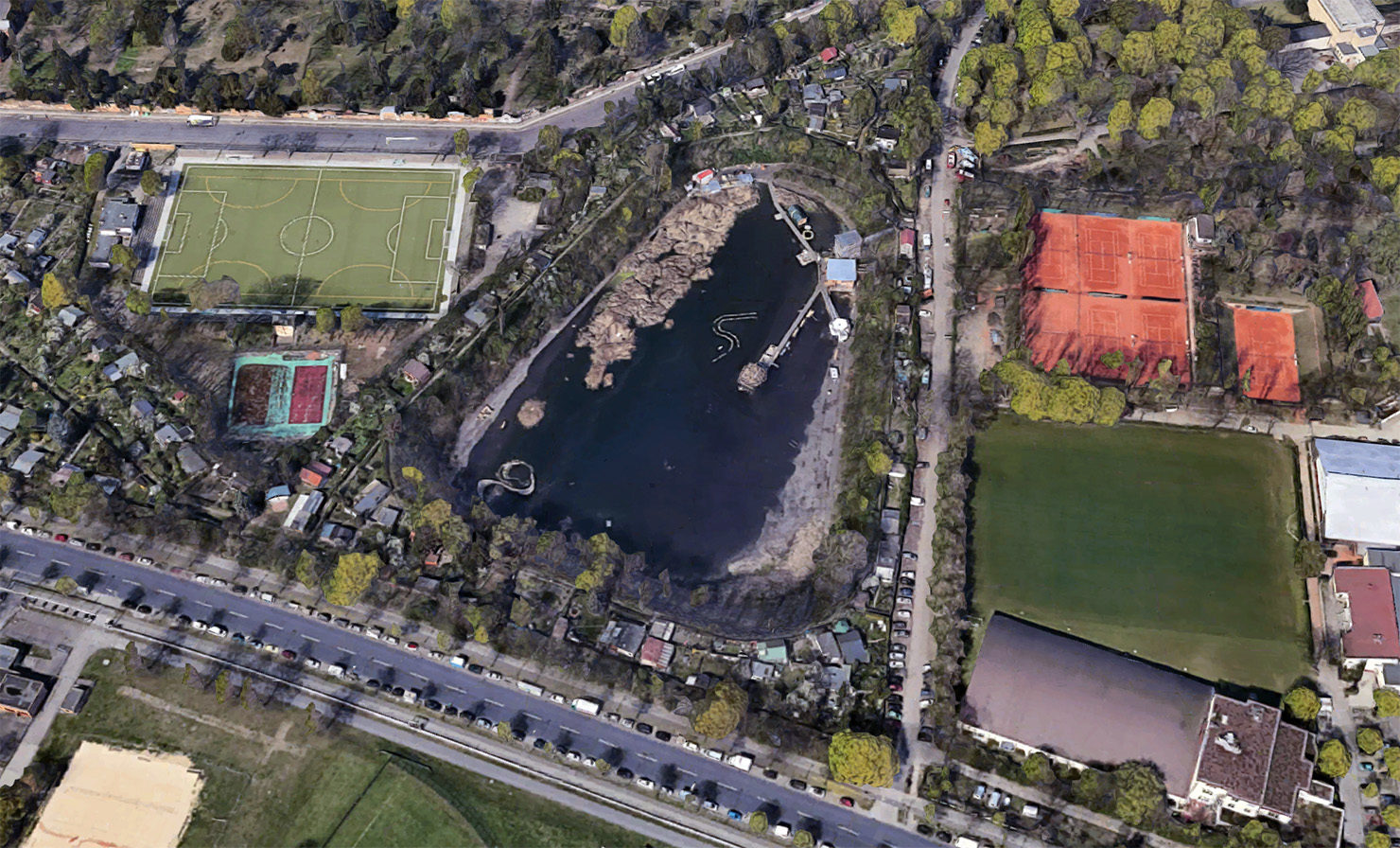

Fast-forward to August 2019: for the fifth edition of Way Too Concrete, we were invited to host a special event on the closing evening of the Climate Care program of the Floating University Berlin, curated by Gilly Karjevsky and Rosario Talevi. Initiated by Raumlabor, the project is described as a “temporary, inner-city laboratory for collective, experiential learning and transdisciplinary exchange”. It inhabits a rainwater runoff basin serving the now defunct Tempelhof airport.

The site, which is experienced as a peculiar hybrid space somewhere between artificial reservoir, and natural pond, does habitually flood after rainfall, as you can see above. An uneasy calm defines the basin, which is encircled by allotments, and sits several meters below the surrounding land. The sense of calm stems from the periodic presence of water, the surrounding trees, and the reeds growing in the basin. Wildfoul pass the time here. The hollow shelters the visitor from the sound of the city. But the uneasiness arises perhaps from popular images which haunt the imagination: one is thrust, unwittingly, into an Andrei Tarkovsky film. By reconfiguring the site, Raumlabor have created a poetic space, drawing attention to the uncanny interplay of human artefact with the ever unwinding logic of natural systems. Tarkovsky has said that a “poet is someone who uses a single image to express a universal message”. The message put forward here is that of the value of care in the context of an unfolding climate catastrophe.

Regular editions of Way Too Concrete avoid thematic coherence, and where any is to be found it is usually accidental and more often than not identified by our guests as the event proceeds. Edition five was different because Gilly and Rosario invited us to explore the theme of “Icebergs”.

For some more insight into the Floating University, jump here.

What follows is a transcript of the talk I gave on Saturday 10th August 2019. Occasionally I address the audience as “you”. Consider yourself part of the event, ex post facto.

Since Part I of this article was published, I have devoted a considerable amount of time to researching the landscape of the Teltow Plateau and the kettle holes which dwell in it. The Floating University talk was the first expression of this research, and combines descriptions of walking through this landscape, with geo-history, reflections on cartographic representation, and fictional segments which weave local myths into the whole narrative.

1. Out Walking

Where are we, actually?

And, whilst we’re at it: when are we?

For the sake of convenience, you might simply answer “here” and “now”. But something tells me you’re not looking for convenience this evening. After all, you’ve decided that the best way to spend a Saturday night is crouched down in the rainwater runoff basin of a former airport.

Take a moment to reflect. Look around. Breath.

So whilst the questions might sound a little trite – disingenuous, even – your own choices this evening seem to have been shaped by a curiosity about the role that space and time play in your lives.

For me, a heightened awareness of my relationship to time and to my immediate environment has been prompted by a series of looping, overlapping walks through Berlin’s southern districts: Tempelhof, Steglitz, Mariendorf, Britz, Bukow.

It began by accident two years ago, with a stroll. An old friend was visiting Berlin, and we set off together, anguished by the Brexit referendum and a looming Trump presidency. We wondered aimlessly for several hours, setting out over Tempelhofer Feld, traversing unfashionable parts of Neukölln, and vaguely following the path of the A-100 Autobahn and the Teltow Canal into neighbourhoods that felt both unremarkable and exotic at the same time. The surprise, always, with Berlin, is that there’s so much of it.

Toponymic street names like Oberlandstraße, inspired by long-lost landscapes, disclosed themselves in puffs of significance. Several water-themed landmarks en route tentatively hinted at mythical aquatic narratives obscured by industrialisation, urban expansion and recent economic neglect. By walking through it, slowing the pace, and momentarily discarding our transactional relationship with the city, we glimpsed an older fabric. The city revealed its deep past, offering up traces of an ancient forest path, a chain of medieval villages, and above all, the notion that arbitrary boundaries defining space, place, and time could be transgressed by something as simple as bipedal motion.

However, by the end of the day, our heightened sense of a subtle local fabric was upended as we sat down for a drink in a gigantic Californian investment project on the edge of Mariendorf. The Stone Brewery, inhabiting a former gas works, sits in the shadow of a Britsh-built, Victorian-era gas container, and is watched over by the company’s horned devil-face logo, which stares into the setting sun, from the radial spokes of a rose window.

Retracing the walk on a map that evening, I realised what we’d done. As if in response to the gloomy political backdrop, we’d unconsciously been looking for higher ground – an overview, perhaps – finding relief on the giddy heights of the Teltow plateau, a full 10 meters higher than Berlin’s city center. It was as if we’d responded to an inner disposition – a sense of unease – by using the topography of Berlin as a medium to describe a more favourable state of mind. We didn’t want to drain the swamp. We just wanted to crawl out of it.

Captured by this possibility, I began recreating the walk – first on my own, then in groups – adding diversions when they suggested themselves. The walks were becoming a meditative communion with a much older landscape, hidden just below the surface of the city.

In her 2018 book Timefulness, the geologist Marcia Bjornerud maintains that “to think geologically is to hold in the mind’s eye not only what is visible at the surface but also present in the subsurface, what has been and will be.”

I’ve begun to see the walks as a constantly unfolding continuum of space and time. Any new single walk is absorbed by the larger Walk, with variations of the route an irrelevance, since the Walk attaches no meaning to a starting point or an end. There is no route, just territory. There is no time, just duration.

In becoming more intimately acquainted with the city’s subtle, underlying topography – the mechanisms which shaped it; the cartographers who mapped it; the artists who depicted it – a spooky kind of polytemporality follows me about town.

It’s now possible for me to turn a corner in Schillerkiez, and find myself in the Rollberge – those rolling hills – of Johann Georg Rosenberg’s 1785 view of Berlin, from what will soon become Hermannstraße. The polytemporal allows me to move through time in several spaces at once. In fact, I’m out there walking right now; only you won’t have noticed, because you’re out there too, walking with me.

2. Schneider’s Hatchings

On one occasion it occurs to me that The Walk might benefit from using maps which are several hundred years out of date. I’m not yet sure why, but the idea instinctively feels good.

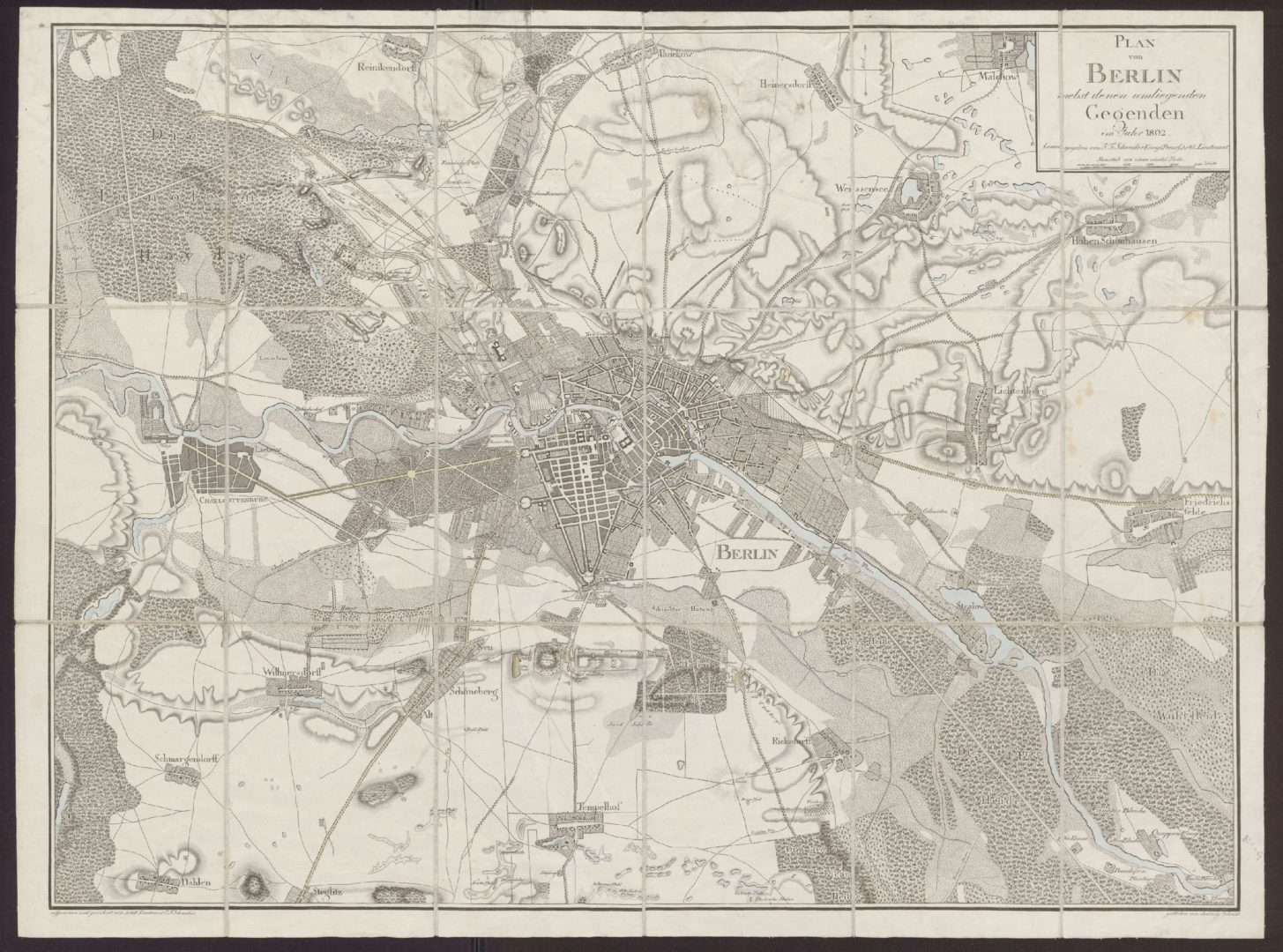

From a collection of historical Berlin maps, I acquaint myself with three-and-a-half centuries of cartographic representation.

Until the late 19th century, many of the maps are identified by the names of individual cartographers. Memhardt, Schleuen and Wolf; Schneider, Boehm and Straube.

In 1652, Johann Gregor Memhardt depicts the market towns of Berlin and Cölln, on opposite banks of the river, surrounded by a broad moat. The map is oriented north-east, putting Berlin at the top of the page. Perhaps it already senses its own destiny.

Schleuen’s map of 1769 must be turned almost on its head before we can relate to it. He gives us a city expanding south and west, enclosed now by a defensive wall which gave us Kottbuser Tor, Brandenburger Tor, Schließisches Tor.

Schleuen extends the boundaries of the map well beyond these city gates, thereby relating Berlin to its immediate environment. Forests and marshlands are warranted much attention, but large areas of unmarked land seem to hint at territories earmarked for metropolitan expansion.

But it is J. F. Schneider’s map of 1802 which has become my standard guide for walks in Berlin’s southern districts.

Why should that be?

Perhaps because it is the last topographic map which shows Berlin and its surroundings largely untouched by industrialisation. No railway lines, no canals, and accredited to an individual, not a royally appointed military committee.

The lie of the land is imbued with pre-industrial thinking. Schneider offers us a last glimpse at an unquantified landscape. It represents a form of spatial knowledge which still uses the language of myth and narrative to describe our relationship with our environment.

Protuberances and depressions in the land are suggested by hatched radiating lines. It can be difficult differentiating between between hills and valleys, but there is something visceral and immediate in these markings: an expression of subjective experience, not of mathematical analysis.

The hatched lines are important because they operate anecdotally, as an expression of how the environment is perceived by the body. In contrast, the contour lines of modern maps, with their precise grading of elevation above a theoretical sea-level, presuppose actions to be taken upon the land: circumvention, penetration, extraction and commodification. All the processes which have helped to hide the topography of Berlin under the things we call Berlin.

Schneider’s hatchings are not the only detail which suggest an alternative reading of the Berlin landscape. My eyes are drawn to the bottom of the sheet, far from the city center, and towards the literal edge-lands, a periphery in the waiting.

Nestling in a string of elongated depressions, a chain of ponds and pools is discernible. By fading out the surroundings, a pattern becomes apparent: a giant aquatic landscape comes to dominate my perception of the region. It is impossible to ignore the east-west orientation, suggestive of ancient geological forces. And it is hard to resist the temptation to see the collection of ponds as a discrete place unto itself.

And perhaps this is why Schneider’s map has become central to the Walk. Not because of a nostalgia for what is lost to time, but because it enables the Walk to generate new readings of the city based on a different set of codes.

To consider the ponds as a coherent setting is to reimagine urban geography as a set of spatial possibilities unconstrained by streets and buildings. To consider the ponds as a common ecosystem, is to readjust our species-centric view of the urban environment. And to consider the ponds as charismatic witnesses to geological timescales is to question the permanence of our endeavours, and to find humility.

3. Kettle Holes

I come to learn that the ponds are actually ”kettle holes”; geological features of the last ice-age. The so-called “Weichselian Cold Period” began 115,000 years ago. Glacial ice spread south, reaching its maximum extent just south of Berlin around 22,000 years ago. Around 11,000 years ago temperatures rose, and the ice slowly – very, very slowly – melted away.

Imagine Berlin for a moment, during the centuries of glacial retreat. Imagine a shelf of ice almost 200m thick, fractured, craggy, stained with algae and dirt, tapering down to a boggy landscape flooded by torrents of meltwater in summer.

A broad river has formed at the foot of the ice sheet, flowing from east to west, flushing away all the sediments pushed into place by the ice 100,000 years earlier. Imagine mammoths too, and woolly rhinoceros and musk ox grazing on the raised plains just south of Tempelhofer Feld.

And imagine too, the river banks of this great, frigid, slow-moving body of meltwater. Not as difficult as it might sound. You’re sat on the south bank of this ancient river right now.

If you’ve ever cycled up Prenzlauer Allee, cursing the incline, then you’re already well acquainted with the north bank. And if you’ve ever freewheeled down Meringdamm towards the appropriately named Bergmannstraße, then you’ve already celebrated the remnants of this ice-age river.

When the glaciers began to melt, enormous chunks of ice would break off and crash into the soft earth below. Their huge weight pushed them into the ground, and later they would be buried by layers of windborne sand and dust.

Does an iceberg need an ocean? Does an iceberg need a witness? Does a calving iceberg make a sound when no-one’s around?

Caked in dirt, these shipwrecked icebergs remained entombed, slowly thawing for a thousand years, until at some point, all that remained was a pond.

4. Blanke Helle

Approached from the east, Erich Glas and Hans Jessen’s 1929 residential estate in Tempelhof offers few clues to the passer-by about the specific topographic context of its setting. Street names memorialise Saxon military leaders and Lombard Kings rather than immediate geological traits. But locals have long referred to the area – with dry Berlin irony – as Tempelhofer Schweiz, on account of the rugged terrain which was still apparent until the early 1900s.

One October I find myself here by accident. I’ve drifted from Alt-Templehof with a vague notion of finding the Teltow canal.

A low-slung portal at the end of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Straße frames a deep interior courtyard, through which one can pass to the street beyond. I’m drawn inwards, pulled along by the perspective-tug of the landscaping, and I find myself reflecting on an encounter in the graveyard of the Tempelhof Village Church that morning.

The church is hidden from the main road, tucked away behind a branch of Woolworths. It was founded in the year 1210 by Templar Knights, who were granted land here, and established a commandery on a promontory between two ponds. Their insignia can be found on the steps leading from the graveyard down into the swampy bowl of Wilhelmsteich.

In the graveyard I’m approached by a tall, slightly stooping figure wearing a wide-brimmed sun hat. Her face is half obscured by a blue-black floral print scarf. A dewy right eye fixes me in a benevolent stare, and with a voice which reminds me of hand-bells, the figure asks for my help with two large watering cans which have been filled to the brim from a dripping tap poking out of a tangle of ivy.

“Können Sie mir kurz helfen?” the figure asks. “Wasser ist so furchtbar schwer.”

I follow her, the two cans sloshing, as the figure strides off through the yard with a long bamboo cane in one hand. The figure’s feet are partially obscured by a loose arrangement of wrapped garments, which might or might not be sewn-together shirts and other scraps of fabric, arranged in such a way as to render one half of the body dark, and other other half pale.

As I set the cans down, the figure tells me apropros of nothing, “Eis ist aber leichter als Wasser.” Maybe I misheard, but I nod in agreement. We are stood in front of a memorial stone for the Berlin and Brandenburg victims of the 2004 tsunami. I water the plants.

Uneasily recalling the encounter, I find myself on the other side of the courtyard, crossing a street which curves around a deep depression in the land. This is Alboinplatz, site of a pond called Blanke Helle. The housing development wraps around the pond, forming an amphitheater.

I descend into the bowel, captivated by its singularness, its suddenness. The pond itself lies surprisingly low. Standing at the water’s edge, it’s easy to imagine how its cold murk once filled the pit to its brim.

At the southern edge of the pond, a gigantic stone sculpture of an aurochs watches over Blanke Helle, head dropped, haunches tense, as though contemplating a leap into the water. The sculpture was created by Paul Mersmann in 1934, as part of an NS-era job creation scheme for artists. But perhaps it was too pagan for the Nazi regime: the authorities refused to officially approve it, demanding its removal in 1936.

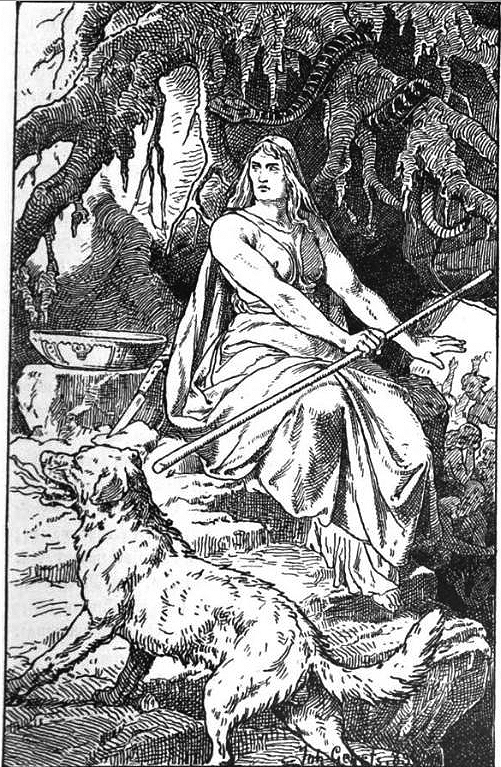

The aurochs makes reference to a local legend. A long time ago, when the area was covered in dense forest, a pagan priest lived near the pond. On a sacrificial alter, the priest would make regular offerings to Hel, the goddess of the underworld. Raising his hands over the oblations, the pond would begin to shake and to foam, and out of its depths two mighty ochsen would appear. The priest would harness the two animals and put them to work plowing his fields.

When the fields were ready for planting, the priest set the ochsen free, and they would return to the underworld. The harvest was good, and the priest had enough food for the whole year, and the priest would offer thanks to Hel.

One day a young Christian monk appeared, who had lost his way in the forest. The pagan priest kindly offered shelter to the monk, and believed him to be a sign from Hel that his time was up and that he would soon die and be taken to his final resting place.

The priest instructed the monk to look after the holy site, and encouraged him to make offerings to Hel, and passed away some time later. But the young Christian monk ignored the priest’s advice, and made no offerings to Hel, fixed in his beliefs. When the crops failed, food became short, and the monk prayed to God for salvation. The pond began to shake and to foam, and the two ochsen appeared from the depths. They strapped themselves into their harnesses and began ploughing the banks of the pond over and over again, so violently that the fields were destroyed and the ground began to sink. The water level dropped, and a hole opened up, big enough to swallow the monk, the sacrificial alter and the ochsen back into the underworld.

5. Toteisloch

How are myths born? Perhaps local pagans invented the story to undermine the missionary zeal of the Templar Knights: a medieval disinformation campaign.

Traces of urban resistance to the pagan threat of local geography come in the form of Christian hero narratives: Alboin, Arian King of the Lombards in 560 AD, is appropriated by name for the streets which surround Blanke Helle, and as an image on the tower of the Alboin Kontor just down the road. The placement resembles an act of deliberate encirclement and surveillance: the Christianised-military-industrial keeping the pagan in check.

The brain systems which deal with spatial orientation also support learning, memory and cognition. Walking is thinking: it allows us to make connections. In a recent publication, Shane O’Mara, a professor of experimental brain research, writes

“The timescales that walking affords us are the ones we evolved with, and in which information pickup from the environment most easily occurs.”

I’m beginning to think I might have overdone it, though. I begin assigning mystical significance to graffiti.

On Gneisenaustraße, just under the shoreline of the ancient river bank, someone has sprayed a polytemporal, geospatial reminder:

And near Kottbuser Damm, a road originally built as a causeway through marshland, a foul-mouthed wall – in fact, an hallucinogenic post-pagan urban oracle – bears scrawled witness to HELL, HOLE and LEER amid a compendium of obscenities

The term “kettle hole“ has an enigmatic ring to it, but I like the German word: Toteisloch. Three blunt monosyllables convey everything you need to know: dead ice hole; HEL HOLE LEER.

The few images we have of goddess Hel depict her on the edge of a fiery Christian idea of hell. But in Norse mythology the underworld is an icy place, as I am reminded in the picture caption of a story in Iceland Magazine, concerning the Icelandic Naming Committee’s rejection of an application by parents to name their daughter Hel.

6. Weak Portals

On the banks of Blanke Helle, members of the Geomancy Society of Berlin can be found, alert to ancient energies, dressed in Nordic hiking wear. A deep yearning informs their quest. What can Blanke Helle’s waters still reveal to us today? Which modern, integrative methods can be used to better encounter the mythical substance of setting? The society’s website proposes a specific methodology:

“A transformation can result … from Gaia Touch Body-Cosmograms which have water as their content – a practice which can connect us to our dolphin consciousness …”

You can take things too far, I think, on another day, crouched down at the edge of a different pond – Rothepfuhl – listening to frogs whose calls are drowned out by the sound of lawnmowers and hedge trimmers, sculpting and domesticating.

Rothepfuhl, like so many of the kettle holes, exists in an uneasy state between human oversight and abandonment.

The kettle holes are seductive because they are hard to classify. They are too small to be considered lakes, so avoid the trappings of human leisure; but they are too large, too unwieldy to have been subsumed by back gardens of single-family homes, where they would have been tamed into quaint water features.

So they are scattered, in the gaps. Most are accessible by foot, but some are hidden: behind low walls; wedged between corporate real estate; integrated into the courtyards of 1930s housing developments: the Meltwater Walker could demand a key, access should be granted, but their seclusion is part of the enigma.

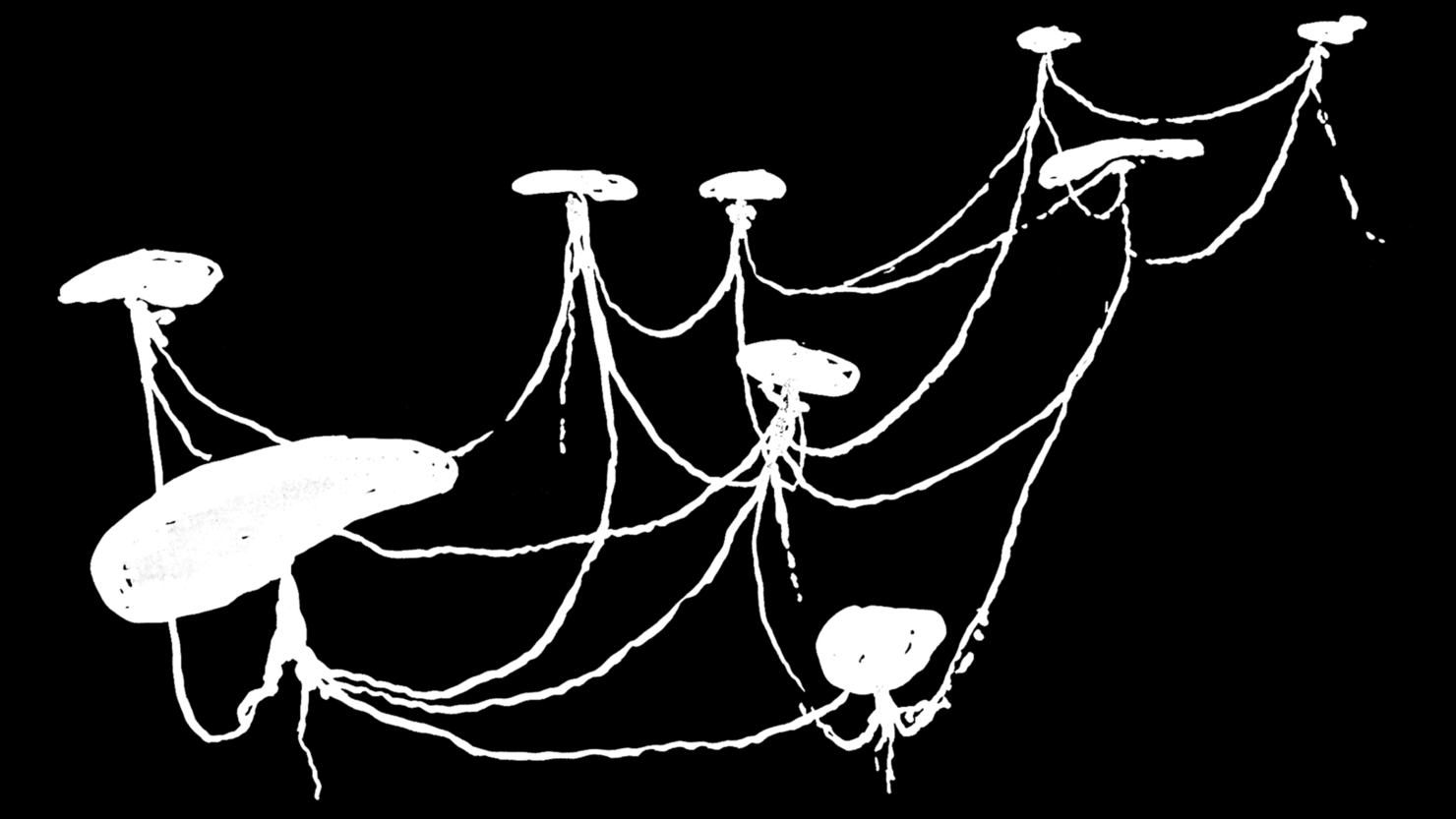

Perhaps pagan deities have it easier. Someone suggests that the kettle holes are portals, connected to each other by spooky subterranean tendrils. Sketchbooks on the night stand fill with diagrams.

A deity, a very bored deity, might use the ponds as a messaging system. A hellish aurochs might take a detour, pop up out of a different pond, and spend an afternoon gallivanting around Steglitz or Britz. I expect the sub-surface travel time between ponds to be instantaneous, a function of faith rather than spatial geometry.

I get up to leave, and a dog-walker startles me. It’s her again. The tall, stooped figure, wrapped in shirts. Dark on one side, pale on the other.

“Water is heavier than ice”, says the dog-walker, by way of greeting.

“I think we’ve already met”, I say.

“True,” she says. “You’re on the right path, but you’re barking up the wrong pond.”

“I see,” I say.

“You don’t see,” says Hel. For it is Hel, obviously, manifest as a dog-walker from Mariendorf.

“What else can you tell me?” I ask.

“Born of ice, not fire. This you know. Stranded now, in the imagination of fools.”

With some difficulty, she leads me back up to the road. Today I notice that Hel’s feet drag through the earth. When she stands still, her feet are immersed up to the ankles in paving stones. She flickers and fades.

“Not my medium,” she says, by way of explanation.

“Why are you stranded?” I ask.

“Weak portals,” she says.

7. Watery Familiars

Washed across a continent by the flow of ice, Hel had her moment. I imagine that deities phase-transition into existence on a wave of faith, and then never really leave us. Instead, they dilute and linger on as unreliable incarnations with no advocates.

With little else to do, Hel meddles in local affairs. It turns out she is the best kept secret of Berlin’s real estate market, and freelances as a geomantic consultant to property developers, investment fund managers and occasionally, members of Berlin’s Senate Department for Urban Development.

Avoiding sensation, she appears to her clients not in the vivid dreams of REM sleep, but as whispered reports in those restless moments shortly before waking. She influences the prevailing mood; nudges dispositions. She takes credit for the prevalence and distribution of DIY super-stores and shopping malls and claims to have had a hand in the headquarters of the Bundesnachrichtendienst. No-one talks about it, of course. No-one wants to be called crazy.

Hel reveals this to me in Franckepark, named for Theodor Francke, a merchant who made a fortune in the late 1800s bleaching ivory. Before the park: an outdoor storage area stacked shoulder-deep in elephant tusks, and, a kettle hole.

In 1900, construction work on the Teltow canal caused the groundwater to shift, and the pond bled out. Many surviving kettle holes faced the same fate. Others were obliterated entirely: a convenient chain of low-lying hollows which could be joined together by digging machines and hunched men with spades. Reports from the time note how canal diggers would uncover prehistoric antlers of deer and moose … and also, the skulls of aurochs.

Fallow deer, temporarily at home in Franckepark [as of 2017, ed.], native to northern Europe in the last interglacial period, watch over what remains of Francketeich.

Meanwhile, traces of aquatic animals – living, dead and imagined – populate the urban environment: as fountains, sculptures and mouldings above doorways. They provide us with distraction, amusement and bond us to our dwelling spaces: but a coherent mythical narrative stretches the imagination.

Hel has vanished. A relief. I wouldn’t want to be caught conversing with her by the students who I guide one day through the meltwaters. They are gathered around Eduardo Rossi’s “Boy With Octopus”, a bronze, cast in Naples in 1900. It shows us an interspecies struggle: one aquatic and one land-bound. The octopus seems intent on engulfing the boy’s arm, or becoming part of its host.

Elsewhere, totems to watery familiars have been abandoned. On Oberlandstraße, again, in the courtyard of Gustav Hochhaus’s 1931 housing estate, stands the Märchenbrunnen, once known as the Delphinbrunnen.

Its triangular plinth supports tall arches of Oldenburg brickwork. The impression is hybrid: an expressionistic, mystic-pagan, Gothic cathedral mashup. One wonders exactly what kind of a Märchen (fairytale) is being told now. A brief note on the website of Berlin’s Monument Authority explains that, due to unspecified damage, the fountain no longer works, and that the ceramic figurine of a boy riding on the back of a dolphin, accompanied by a cohort of turtles, is lost. The fairy tale is one of a modern ruin.

8. Basin

Where are we, actually?

And, whilst we’re at it: when are we?

The rainwater basin appears as a doppelgänger, a supernatural entity, a crude model of nature, a contingency proposition. A simulated kettle hole where the implication of an iceberg is celebrated in totemic form in order to accommodate for its absence.

Perhaps we’ve built an alter.

Hel has not yet returned. It occurs to me that she might not be Hel at all, but an apparition of the rainwater basin. An infrastructural deity. If so, I wonder what new myths might incur, as a consequence of this concrete godhead.

Recently [June 2019], the Senate Department for Urban Development published a map of Berlin’s most hidden waters: the water beneath our feet, beneath the streets, beneath the basements and tunnels and pipes. Groundwater temperatures are on the rise. Geologists are concerned. Deep beneath Steglitz, a significant hotspot has been measured. ●