Meltwater Peregrinations I

Spandex temple knights

Joe was in town, and we went walking. Joe is my doppelgänger of sorts, which suggests the duplicate, but also motion. It might be better to describe him as my stunt-double, living a life approximate to how my own might have played-out had I stayed in the UK. Joe comes from the Black Forest, and was completing his MA in communication design in the UK, just as I was completing my BA in the same discipline. He settled in London. I emigrated to Berlin.

Whilst noting these cultural transplantations over coffee some months back, it became clear that we were now forced to review our lives through the grubby lens of Brexit, that calamitous antithesis to our respective biographies. Since we last met, a few dozen months ago, the world had staggered into a new era. May’s rudderless oblivionism, Trump’s bozo-kleptocracy and Putin’s rule-by-obfuscation were having the worrying side-effect of making Merkel’s strategy of “asymmetric demobilisation” [1] seem like a desirable advancement for democracy. Instinctively perhaps, as though searching for some kind of higher ground or an overview, we headed up to Tempelhofer Feld, Berlin’s former inner-city airport, now a public park and refugee shelter.

Tempelhofer Feld: parade-ground, airport, spandex test-resort

The Nazis built Tempelhof airport in typical geography-scale immensity. The terminal building looks terminal: nothing should have come after it. From a low earth orbit it might conceivably appear inviting, like the docking-station of a planetoid-sized electrical appliance. It’s belligerence is perhaps hereditary: it was erected on the site of a huge Prussian military parade ground. Earlier still, the land was part of a larger tract entrusted to an order of the Knights Templar, whose presence can be heard in the name: in 1200 or thereabouts they founded the village of Tempelhove (Temple’s yard) on the northern flank of the forested, sparsely populated Teltow Plateau.

At the end of the last ice-age, the Teltow Plateau rose up out of a vast meltwater river fed by retreating glaciers. It and the Barnim Plateau a few kilometers to the north define the swampy basin in which Berlin later took root. Two patties of pond-dappled clay, still perceivable today as steady inclines in the districts of Kreuzberg and Neukölln, Prenzlauer Berg and Friedrichshain.

With hindsight, and a weakness for the figmental, it seems plausible that Joe and I had been drawn upwards by subtle topographical indicators (the slant of the coffee in our cups), signalling a way up and out of the perceived political morass of our times. The café where we met is located at the foot of the ancient southern river bank. The name Berlin stems from the Slavic word for swamp, “Br’lo”, and it was out of this that we felt compelled to stride. Did twelve millennia of geomorphic change and anthropogenic drift represented the scale of context we needed in order to accommodate the present with any degree of calm?

On the old airfield, yolks of heathland stretch between the former runways. Skylarks bob out of the undergrowth in celebration of spring’s belated, crashing arrival. Leisure-class humans were celebrating their day of rest by revelling in the various configurations of wheels available to them for traversing short distances with as much elaboration as possible: kite-boards, long-boards, rollerblades, triathlon-bikes, tricycles. Even unicycles, piloted by precocious seven-year-olds, were scissoring about. A fiesta of ball-bearings, spokes and spandex. Strolling seemed a bit subversive, an affront to technique, a slight against every form of enhanceable, quantifiable recreation. How to improve upon the stroll other than by embracing its inherant resistance to optimisation?

Ordnance survey

At the eastern end of the shorter of the two runways (09R/27L), Joe and I cross a patch of land where rows of defunct landing lights are held aloft on small, fenced-off platforms. The ground has been turned, prepared perhaps for some low-key landscaping project. We come across a rusty, dirt-encrusted sphere with a cylindrical appendage. It looks like a grenade. We wonder which public-service phone number might deal with unexploded ordnance. Perhaps unwisely we go for lunch instead.

Playdrive arsony

In the Schiller neighbourhood, we order Schiller Burgers at the Schiller Burger Bar. Sat outside at roughly hewn tables, we enjoy the perverse symmetry of the backdrop: the charred, melted wreckage of a Schiller-Burger-branded Smart Fortwo in the gutter. Car-grilled, toasted. Its burst windshield sags like a grease-drenched napkin, wisps of frazzled upholstery still cling to the skeletal remains of its bucket seats. Behind the car, a trail of scorched fragments stretches out into the road, as if it had been calmly parked whilst dramatically and terminally aflame. We speculate on the motives for such an attack: A skirmish in the war on gentrification, with the burger as signifier of malignant socio-economic forces. But perhaps the arsonist was making a philosophical point, synthesizing J. G. Ballard’s psychosexual auto-erotica with Schiller’s notion of Spieltrieb, or “play drive”: his unification of sensual and rational curiosity. Burning as learning. The dead Smart appears to be an outline for a hyper-local sci-fi narrative in which artisinal burgers will be grilled over the cobalt flames of self-immolating delivery drones, guided by the narrow-band whispers of hunger-prediction algorithms.

Walking the upland

We continue south into a semi-industrialised peninsular of suburbia wedged between Tempelhofer Feld, the A100 federal highway, the Teltow canal and railway lines which encircle the inner-city and once transported its domestic waste to outlying landfills. Yet amidst all these connecting arteries, the place feels appendicized, atrophied.

The payoff for walks guided by subliminal tokens (and the prize for shunning maps), is when the urban fabric begins to volunteer its neglected memories. Street names abhor metaphor, but a susceptive disposition is needed to adjust to their austere poetry. So when we hit Oberlandstraße, or Upland Street, it was clear that this simple toponym was confirmation that we had found our higher ground. We were in communion with the deep topography of the Teltow plateau. We were tuned to the ancient energies of meltwater peregrinations.

High-water mark

Joe mentions that he rents storage space on Oberlandstraße. But the flash of recognition is followed by disorientation. As we begin to head into the afternoon sun, it transpires that his mental map of the area has been formed at the road’s western intersection, whereas we were joining it at its easternmost point. His Berlin is momentarily flipped, south-up, like in the earliest maps of the city. Disorientation and self-storage sound to me like sure indicators of the peripheral, along with the tire shops, crane rental yards and heating-oil dealerships clustered along the canal. Anything which can be sold by the tonne or rented by cubic meter finds its economic niche here, safely above the high-water mark. But Berlin’s peripherality seldom demarcates the limits of the urban: it tends to bloom in tight clusters, confined by stronger forces, like moss in the mortared grooves of a brick wall.

Berlin’s peripherality seldom demarcates the limits of the urban.

One such strong force is the A100, Berlin’s stunted ring road. Work began in 1958, three years before the Wall spliced the city in two. In the earliest days of division, Western moral certainty held on to the narrative that Berlin would soon be reunified, and the A100 would encircle it like a wedding ring. The Cold War took a bit longer than the road’s masterminds had anticipated, but work progressed well into the 1980s, with the highway eventually girdling much of West Berlin. By the time reunification came, the population was suffering from utopia-fatigue. Completing the ring became impossible, with each sign of political intent swatted down by residents. Too costly the affair, too destructive for the communities affected by its course. The current and final phases will connect Neukölln with Friedrichshain (bridging the plateaus) at a cost of 130 million Euros per kilometre. And there the project will stall: a 270° arc of asphalt, an oxbow-motorway.

“So – come up to the lab / And see what’s on the slab.” Rocky-Horror-Modernism.

On Bacharacher Straße, having lagged behind Joe to fiddle with my camera, I find him standing aghast in the middle of the road, staring at an Italianate-style single family home the colour of off-brand vanilla ice-cream. He seems to be recalibrating his aesthetic world-view. Just as I’m beginning to offer a withering summary of Slab’s long and complex relationship with this kind of thing, the full tableau emerges. The Italianate folly is part of a three-house ensemble, each based on the same shell. One has undergone a vaguely Anglo/French makeover, with a vestigial mansard pitch to the roofline above the porch, and a faux-Edwardian garden fence. But the central house, a spec-box with few surface features, reveals the ensemble’s true genealogy. As a pure expression of the typology’s core functional specifications, it indicates that the pitched roofs and accoutrements of its siblings have no practical function. It’s a dressmaker’s doll waiting to be clothed by marketing consultants, a prototype, probably sold as “Bauhaus-style” to account for its lack of decoration. Nope: Modernism never went away, it just learnt how to cross-dress.

Dry springs and cross roads

We press on. Joe has introduced a goal to proceedings: the rumour of a brewery with a beer garden somewhere in the south-west. A recommendation, he says. As the afternoon warms up, abandoning the conventions of “drift” is an attractive proposition. At the prospect of beer, our trajectory tautens slightly. I propose a “fierce stroll”: the ambling character can remain, but the tempo is quickened.

The strategy of accelerated serendipity brings us to the courtyard of a 1931 housing complex designed by Gustav Hochhaus, where we discover an angular fountain in the expressionist style nestling in the courtyard vegetation. The triangular plinth houses a concrete basin on which tall pointed arches constructed from red Oldenburg brickwork rises above our heads. This Märchenbrunnen, or Fairytale Fountain, as it’s known, takes its geometric cues from the ribbed-vault ceilings of gothic cathedrals, but its dedication to watery animation feels more pagan than Christian. Like our cross-dressing spec-box houses, the fountain is a synthesis of the industrial and the folkloric. Hochhaus designed it with the sculptor Hans Lehmann-Borges, a member of the German Werkbund movement (motto: “From Sofa Cushion to Urban Development”). Unfortunately, water is missing from the fountain. So too the decorative tortoises, and the sculpture of a boy riding a dolphin which once formed its centrepiece [2], water-bound familiars from another realm.

The fairytail fountain, in the courtyard of the Gustav Hochhaus estate in Tempelhof

The trajectory of our journey superimposed onto an elevation map of Berlin. The white line marks the route undertaken on foot; the black line shows a short journey on the metro. The darker green area is the north-eastern tip of the Teltow Plateau. Central Berlin lies to the north, beyond the edge of this image.

The Upperland Street will bring us to Old Tempelhof. Who brought the Templar Knights there isn’t entirely clear, but Ascanian Margraves along with various dukes and archbishops form the parade of titled suspects. The decision was likely strategic. They had just given the market towns of Berlin and Cölln joint city status, exempting them from taxation [3]. The Templars (we should probably imagine armed monks) were allowed to set up commander’s courts across the Teltow plateau, on sites which would develop into the villages of Marienfelde, Mariendorf and Rixdorf. Connect the dots and a defensive chain of dwellings emerges, intended to ward off any meddling by the Duke of Schlesien or the Margrave of Meißen to the south-east. Christianising the local Slavs was a desirable side-effect.

In the Medieval Period, our route would have taken us through dense forest, but today it is comprehensively asphalted, paved, tiled over. With Old Tempelhof just ahead, and our backs turned to distant Rixdorf, we subconsciously plot the defensive vectors of old disputes, following the silent vibrations of territorial claims imperative to the invention of Berlin. The underlying topography is as obscured now by factories, warehouses and film-studios as it would have been back then by oak, lime, chestnut and birch. Crossing over the railway line which used to haul West Berlin’s household junk out of town and into a landfill on East German land, Joe and I stop and peer down into the cutting. It is flanked by the verdant progeny of that ancient woodland, and strewn with rubbish, yearning perhaps for the distant mound to which it once might have been relocated.

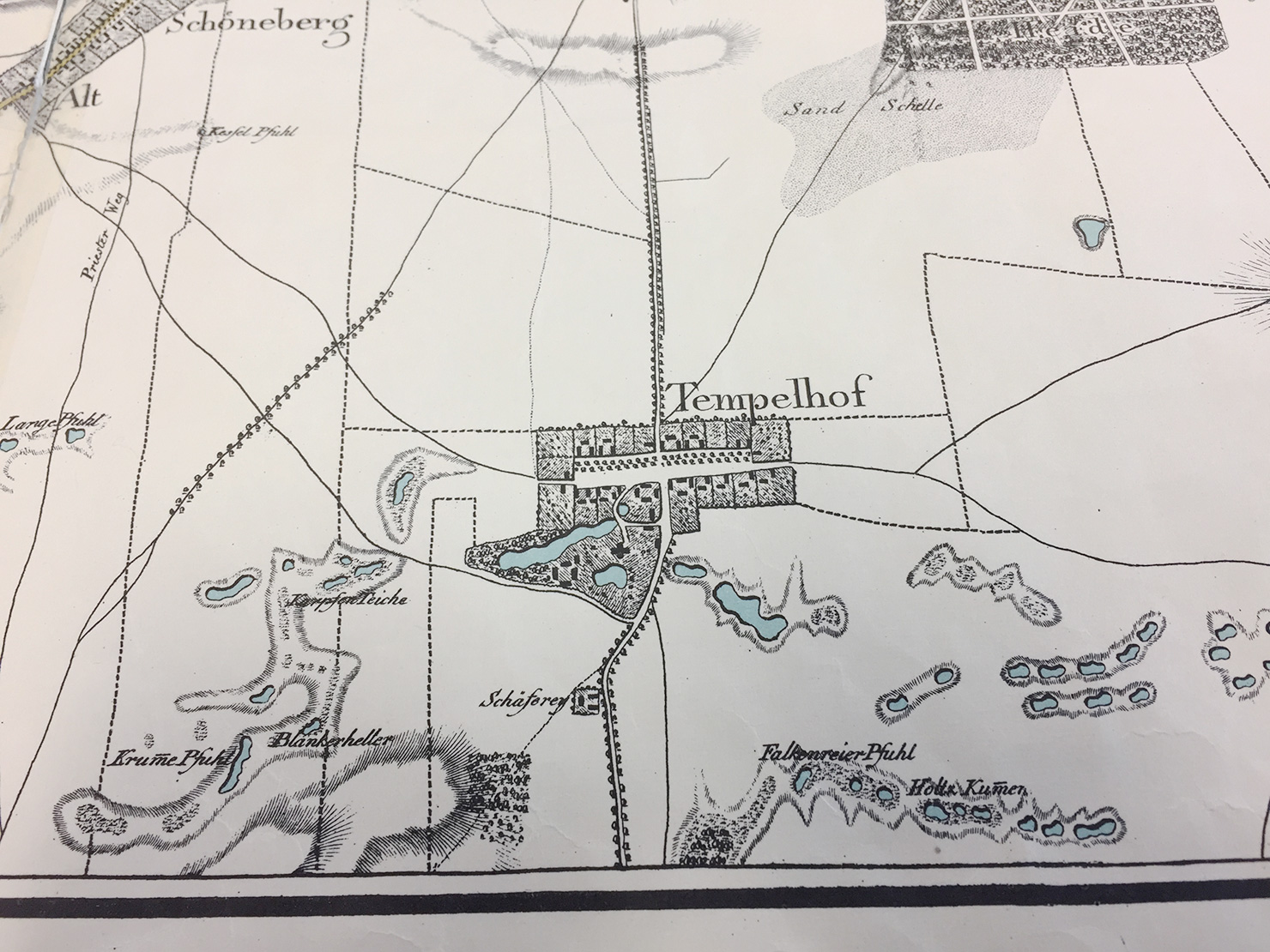

Detail of Schneider’s 1802 map of Berlin and environs

At some point between the Medieval Period and the industrial revolution, deforestation laid the underlying topography bare. An 1802 map by J.F.Schneider [4] puts us in an expanse of nothingness. This terrain-vague – territory described by an absence of the engraver’s tool – seems less like a passive side effect of urban expansion, and more like an active strategy of spatial-production inherent to industrialisation’s expansionist strategy. Maps create territory. Two paths are shown on Schneider’s map, one to our north, connecting Tempelhof with Rixdorf, and another south of the Teltow canal, connecting Tempelhof to Britz. These lines converge in the parking lot of Hansaflex, a hydraulic component manufacturer, meters from Joe’s storage space.

Moraine diving

The two lanes of Oberlandstraße split into four, and peel apart to form a long central reservation overgrown with horse chestnuts, lime trees and various bushes I couldn’t even begin to name, but which seem to be of the type which thrive on suburban diesel emissions or the electro-mechanical fug of the railway cutting. The island describes the historical core of Old Tempelhof, a one-street village surrounded by thin plots of agricultural land (hides) which radiated to the north and the south. The old plots are no longer distinguishable, and are now home to an eclectic mix of austere post-war condominiums, a slatted brutalist chunk of who-knows-what and, closest to the village’s midpoint, a couple of stern Wilhelmenian apartment buildings.

From here Joe and I descend into the pale moraine clay of the Teltow plateau. The metro takes us south to Alt-Mariendorf where we re-emerge through the downward flow of fleece-wearing pensioners. By systemising geographic space, diagraming only the flow through it, the U-Bahn scrambles delicate mental maps. [5] Strap-hanging between portals dug into the ground, we continue to probe Berlin’s defensive flank, obscured by its re-enlistment to the pragmatic reach of industrialisation: villages connected in a synaptic web, drawing rural populations into the urban conspiracy.

Our sense of displacement is anticipated by a bus shelter across the road: it has been designed to resemble feudal-era stables. No such mimicry for McDonald’s two block to the west, or the motor-scooter dealer, or the offset printer, or the next self-storage offering on the skyline.

Our inner-borough snobbery tells us we’re in the middle of nowhere, on the road away from cosmopolitain amenity. But two spherical high-pressure gas tanks looming behind a row of spruces soon mark our destination. We’ve arrived at Marienpark, formerly the Mariendorf Gas Works which for 96 years formed part of the industrial infrastructure of south-west Berlin. A lane takes us passed an old gatekeeper’s lodge and into a vast open space dominated by an imposing brick water tower erected in 1902. Instinctively, Joe and I take it in turns to pose for photos in front of the edifice, recognising its place-making qualities just as Berlin’s Monument Authority have done by preserving it. Most of the surrounding buildings were razed in the mid 1990s when the works were disbanded, but the remaining structures have been given the task of housing new economies, imbuing them with value-adding historical cachet. A little further to the north, sheep graze under the panels of a 2MW photovoltaic plant run by Berlin’s main natural gas vendor.

The author, shielding his eyes from the value-adding, post-industrial, historical cachet. Photo: Joachim Hetzel.

The old gas works are now a branded real estate asset managed by an entity calling itself 4 Projekte ZIM Asset Management GmbH. Marketeers have been busy: Marienpark has a logo (silhouettes of the local landmarks aligned into a lime-green hieroglyph), and an unavoidably bland motto (Raum für Ideen, “Space for Ideas”) which in a clever jujitsu-move, uses its own vapidity as a rallying call for speculation, reinvention, fermentation: Where there are brown bricks, there is inevitably craft-beer. Joe and I are thirsty.

Watering hole

The Stone Brewing Company is intermittently signposted, but we’re too absorbed by the iron framework of a Victorian-era gasometer and the slender, mushroom-topped 1960s New Watertower to care about an orchestrated arrival at the main entrance. We stumble onto the property from behind a fence, and startle five or six apron-clad kitchen staff smoking furtively next to a fire door. One of them indicates the direction with their cigarette and we step onto a huge split-level patio, where dozens of late-afternoon boozers sip beer from tulip glasses, and squint into the sunlight. Where had these people come from? Mariendorf had seemed depopulated; the approach to the brewery was just as quiet. The effect was theatrical. We were entering mid-scene, bystanders to a well developed plot, entirely indifferent to us.

The Victorian-era gas container, manufactured in London in 1900. The ultimate craft-beer backdrop.

Beers arrive, mine inappropriately dark (a black bulb, almost a meal), Joe’s more sensibly attuned to the gold light of the sinking sun and an encroaching crispness to the air. Our friendship goes back a couple of decades, and is happily undiminished by the scant contact we’ve had in that time. At days-end it appeared that the route we had trodden was a physical manifestation of our associative, free-wheeling conversation, a cartography of memory imbued by repressed geography. An urban drift is an act of simultaneous reading and writing, the contribution to a palimpsest of the personal and the communal. Space is thickened time, and passage through it a pan-chronic communion. Curb-stones will talk to you, as will the smoothly tiled perimeter wall of a biscuit factory, the litter in the undergrowth, the tilled soil of unfinished business, the prosaic chatter of street names, the disposition of the tarmac, the basin of a drained fountain.

A still quieter voice, intoned many octaves lower, at allegorical frequencies, kneads our psyche all the while. The plateau drew us upward into its folds, contravening thermodynamic law, gravity and baseline human laziness. It promises a synthesis of the mythical and the transitory modern. More must follow. Above the swamp, on the Teltow Plateau: nothing but broad fields and soft light.

[1] The term “asymmetrical demobilisation” gained popular notoriety in June 2017 after Martin Schulz, leader of the Social Democratic Party, used it in a speech to describe Angela Merkel’s political strategy. More info here (German language)

[2] A full description of Gustav Hochhaus’ estate on Oberlandstraße, including Hans Lehmann-Borges’ Märchenbrunnen, can be found on the Berlin Monument Authority’s website, here (German language)

[3] Cölln was the name of the settlement on the south bank of the river Spree, with Berlin on its north bank. In 1710 the two towns were merged by Kind Frederick I to form the capital of Prussia. The name Cölln lives on today in the southeast borough of Neukölln. Berlin im Mittelalter: Berlin/Cölln unter den Askaniern, by Norbert F. W. Meier. Berlin Story / Alles Uber Berlin, 2012

[4] J.F.Schneider, Plan von Berlin nebst denen umliegenden Gegenden

[5] Guy Debord speculates that the elimination of geographic distance is replaced internally by “spectacular separation”.