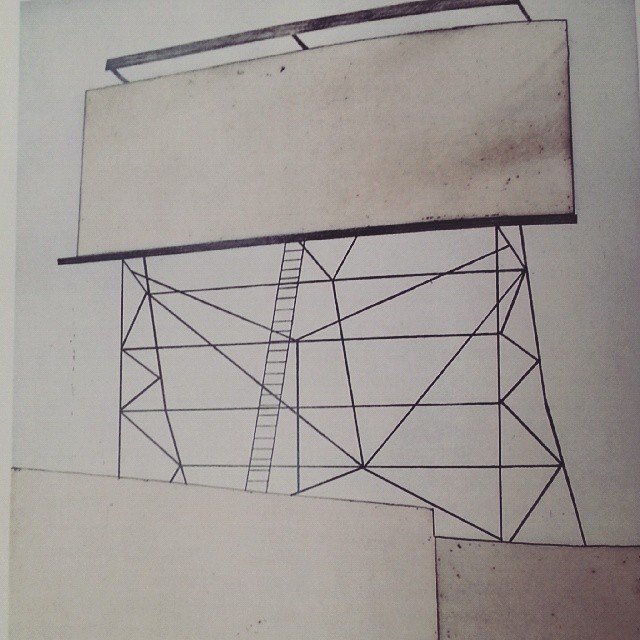

Line Drawing

Christmas Eve. A bright, freezing day. Sunlight is valuable. Up the mountains we go. The destination is the peak of Annaverna, where there is a large antenna, which is just visible over the crest of the hill, right of centre.

On the way up, we pass a dolmen and (in background of picture) a circle of standing stones, arranged in alignment with the western sun. But we suspect that these are in fact recent (19th century?) reconstructions of prehistoric megaliths.

We leave behind this cosmic calendar, however ersatz, and set our sights firmly on the omnidirectional antenna, also a keeper of time and time signals.

The windspeed climbs and the temperature drops with almost every step.

As we approach, the wind makes it difficult to hold the camera steady. We can no longer hear anything. The total noise of the wind blasts our eardrums.

At the top, the whizzing food-mixer noise of the vibrating guy lines adds itself to the din. But the view rewards. Leinster meets Ulster, Republic of Ireland meets United Kingdom (for the time being, at least). The landscape is divided, Ed Ruscha style. The guy lines produce a strange foreshortening. The mountain becomes comprehended as so many data points, subject to transmission. The perspective both plunges and remains resolutely inert, as in Ruscha, the portraitist of axonometric captialist infrastructure. We are totally alone. It is so cold, we can spend no more than a couple of minutes here.

Then all of a sudden a car drives past very slowly, a few feet behind us. It simply appears. A four-wheel-drive American-style pickup, its fat tyres clambering carefully on the line of loose scree that until now we had regarded as a path and now we see is an access road for the maintenance engineer. Is that an open glass bottle on his capacious arm-rest, where his elbow rests, his wrist poised? Is he drunk? It is Christmas, after all. His supervisor won’t be checking up on him today. May as well enjoy the shift. He gives that part-hostile, part-condescending look that outdoor workers give to bourgeois nature enthusiasts such as ourselves, or that people like us interpret in that way as part of the broader outdoor experience. You know nothing, says the look. And you are fools to stand out in that wind when you could be safe and warm in your car, and a little bit drunk too.

Either he is some evil pixie of capitalist efficiency, maintenance and technics who patrols the area, frightening the easily-frightened passerby; or he is a freelance weirdo. He smiles enigmatically, a little crazed, a violent guardian, in his element. In my pocket, my fingers want to take out my one-eyed spirit-stealing light-capturing time-stopping juju. But what would this threatening spirit say, think, feel and – worst of all – do if I photograph him? I cannot take his picture.

A couple of hours later, we’re back on parental duty, patrolling the local playground. The warm winter sun is setting. I call the kids. Soon it will be so cold, we can only spend a few more minutes here.