Some Heavy Posthumanist Architecture Shit

I spotted a “Bologna Centrale” sign through the train window as the sleeper train from Munich coasted into the station. The sign’s squat white letters on blue seemed friendly, almost playful. It lacked entirely the staunch objectivity of fonts used in Germany in public places. It was 5 a.m.

The station’s platforms lay like illuminated piers in a calm sea of darkness. The air felt warm and moist. The train’s arrival briefly flooded the platform with activity. By the time I entered the brightly lit main hall, emerging from the subway from beneath the tracks, the silence had returned. I stepped outside onto the station’s dimly lit square. Silhouettes of people slouched on gray polypropylene benches in polycarbonate bus sheds waiting for first buses. Strips of red LEDs glowed with dysfunct and cryptic messages. Missing LEDs created a new kind of alphabet: As that look like inverted Vs, upside down Ls, etc. The sole source of activity were the flashing lights of the pedestrian crossings.

It would be a while before the first buses would run. So I photographed a decrepit area map with my phone and headed up Via Independenzia towards the city center. I had walked under the city’s famed arcades for about half a mile when the street lights went off, leaving me stumped in near complete, pre-industrialized vampire darkness, a good half hour before early dawn. Was this an austerity measure in light of the European debt crisis? The darkness drove me out into the faint light of the street, where with some effort I could still make out the black outline of buildings and some of their figurines and crenelations against a indigo black sky. Farther up Independenzia, flat white bands of a zebra crossing led like stepping stones across a bottomless darkness straight into San Pietro’s main portico. In comparison with the depth of the church’s baroque facade, the strips had an almost Julian Opie like flatness.

For a while, I wandered the dark alleys and arcades around Bologna’s Piazza Maggiore central square trying to find my hotel. I hadn’t slept enough and there still wasn’t a whole lot of light in the city’s medieval alleys. First encounters with other humans seemed almost hallucinatory. Two street sweepers in perforated green and white plastic vests swept the streets to the beeping sound of a tiny light-gray Piaggio three wheel pick-up in reverse. I zoned out briefly on the hypnotic reflections of the Piaggio’s orange flashing lights on their vests’ reflective 3M strips. The polyurethane wheels on my cheap-ass Samsonite trolley echoed hollow and mute on empty paved streets.

As I left the beeping street cleaners behind, golden axonometric capitals of a beautifully painted sign popped forward out of the residual darkness under a heavy masonry arch: OTTICA A. PAOLETTI. The lettering was squarish, thin and elegant. A perfectly executed gradient on the letters’ extruded sides created a convincing illusion of depth. I stared at the sign for a prolonged time. Residual darkness acted as a filter, illiminating the imperfections my eyes cling to to accept things as real. It appeared almost immaterial, even metaphysical, pure letter, pure signifier. I would shop for optics in a shop whose owner has such a good eye, picking signage that denoted optical precision by standing up to the most scrutinizing visual inspection, to the most exacting optical equipment. During my last examination, my eye doctor had attested to my eyes’ extraordinary resolution, despite my short-sightedness. I was on a Via Clavature, in a cluster of opticians and optics shops very close to Piazza Maggiore. Ottica Paoletti sold premium optics – mostly analog camera equipment, binoculars, sunglasses. I recognized the brushed aluminum of a Nikon FM2 and recalled the swooshing sound of its smooth shutter mechanism. I checked the map on my phone. My hotel on Via Drapperie was just around the corner. As I set off, I felt an anticipation for Bologna and what it would have in store for me. I wondered what effect the city’s physiognomy may have had on Umberto Eco, now professor emeritus of semiotics at the University of Bologna.

I woke up in my hotel room close to noon. Intense sunlight filtered through the gaps of the heavy velvet curtains. I reached for my phone and searched for a quick Bologna primer online. Mentioned there was a pinhole optical device in the roof of the eastern aisle of the city’s main church, San Petronio, on Piazza Maggiore, just around the corner from the hotel. As a camera obscura, it focused the inverted image of the sun every day at noon onto the world’s longest meridian on the church’s floor. After a quick coffee and pastry on Via Drapperie, I passed Ottica Paoletti again on the way to the cathedral. Under the sign’s crisp lettering, a studious looking middle-aged woman in pale green cardigan arranged a few camera accessories in the shop window glancing over reading glasses with transparent plastic frames. The shop’s interior brimmed with activity.

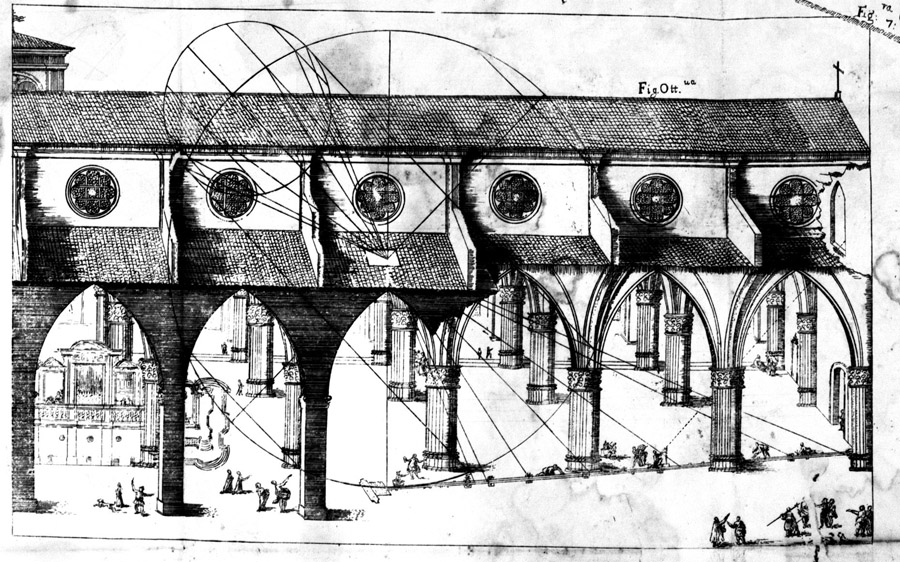

A printed banner depicting the intended white marble finish covered the bottom half of San Petronio’s crude and derelict brick facade. Inside, I spotted the meridian pretty quick, a thin 60m diagonal brass line set in white Carrara against the red marble of the church floor, starting in the western aisle and traversing a line of heavy piers into the church’s soaring nave between piers 2 and 3. An oblong depiction of the sun surrounded a rather small spot of intense light in the ceiling of the eastern aisle’s fourth vault, just above the meridian’s origin. Zigzagging golden rays emanated outward from the glaring speck of light at its center. I had to search a little for the sun’s image and found it a dozen meters west of the meridian. It was around 11 a.m. The light spot was somewhat oblong, skewed by the light’s angle, recalling the oblong depiction on the ceiling. Its halogen blue halo flickered a little and it cast shadows of unnatural sharpness. This kind of sharpness I only knew from the light of projectors. I experienced a similar kind of visual dematerialization, in light of perfection, that I had witnessed in the hand painted sign of Ottica Paoletti, or when looking at a holograph.

It took my pupils a minute to re-adjust to the relative darkness of the church’s interior and until the image of the reflected sun that had burned itself on my retinae had waned. I was now on a Fantastic Voyage. The church had become the eye of a giant sentient being. The church floor was its retina, onto which images of the outside were projected through a tiny cornea in the church’s ceiling. The sentient being was the giant arthropod of the Vatican Church, and San Petronio a ommatidium of its compound, knowledge seeking, eye, scanning dark ages for enlightenment.

I spent the next hour trying to decipher the information on markings along the brass meridian, making out summer and winter solstices, vernal and autumnal equinoxes, and the zodiac signs. I couldn’t make sense of a row of numbers from 1 to 250 and roman numerals from XV to ??. At noon, I stopped my interpretations, transfixed with excitement on the sun’s image as it crossed the meridian. Then a guard in double breasted jacket emerged from the shadows and advanced toward us. He wore his jacket sloppy, as if he had thrown it on quickly. What could he want? Were they really ushering us towards the exits right as the moment of magic that everyone had been waiting for? As cosmic as this event was to us visitors, to the guards, it was as profane as the beginning of their lunch hour. For a moment, I was startled at the thought that generations of church guards over hundreds of years had had their daily rhythm defined by the meridian, briefly sharing this cosmic moment with flows of visitors only to shatter it, asking them to leave so they could take their lunch break. To them, the meridian was nothing more than a giant punch clock.

Perplexed by my sudden ejection, Bologna’s colonnades seemed like mere extensions of the San Petronio’s aisles. It made me think what aesthetic impact such a magnificent structure, essentially a inhabitable astronomical instrument, might have on its surroundings. First, on people’s aesthetic perceptions and then on the architecture they would go on to create in the church’s shadows based on these perceptions. San Petronio’s meridian must have spawned the interest in optics and the optics shops on Via Clavature. What light could the curtains of Via Drapperie have concealed? Azimut investments occupy offices on the second floor of a building just across Piazza Maggiore. Across Via Rizzoli, we found another cluster of shops selling globes in various sizes and materials. The sunlight hit the globes at an angle beautifully, in a way that invoked azimuths and apogees and perigees, again. Bar Sol sells wine in one of the alleys around the piazza.

Had we found a trace of the influence of the city’s architecture on the author of Foucault’s Pendulum? Was its early working title Cassini’s Meridian? The clerical secrecy in the Name of the Rose seemed to recall the Copernican discoveries that resulted from San Petronio’s meridians, initially commissioned by the Vatican for the eventual reformation of the Julian calendar, to facilitate the prediction of Easter, and kept secret during the trials of Galileo.

It’s the beauty and perhaps the tragedy that the influence of things, architectural and otherwise, seems to operate more often than not on a subliminal, unforeseen level, beyond our control as architects or authors, no longer architects of our own vision, but unknowing obsequious servants of bigger ideas silently at work outside of us, the workings of post-humanist architectures.