Paper Architecture

Much of Ireland’s built architecture in the last five years occupies a kind of theoretical limbo inasmuch as it has yet to take on any truly useful life. A happy naïf dropped in our midst might imagine the whole country as being engaged in a fascinating experiment to see what happens to new buildings when they are left idle, in various stages of completion, for undefined periods. The thoroughness of this experiment has meant that the standing specimens encompass entire housing estates, shopping centres, hospital wings and major banking headquarters. This building has been standing incomplete, derelict on Dublin’s North Wall Quay for more than a year. In a way, however, it does have a kind of function, standing as the skeletal monument to hubris, a crypt for the mad, money-driven speculative bubble that has put the whole country in an economic hole, plumbed, so far, to a depth of almost 100 billion Euro.

It was to have been the headquarters of Anglo-Irish Bank (abbreviated to the miserable “Anglo” in everyday speech), the mismanagement of which has so far cost Irish taxpayers roughly 35 billion euro in recapitalisation bailouts. If completed, it would only have been a porcelain crown in a set of expensive ugly teeth ”¦

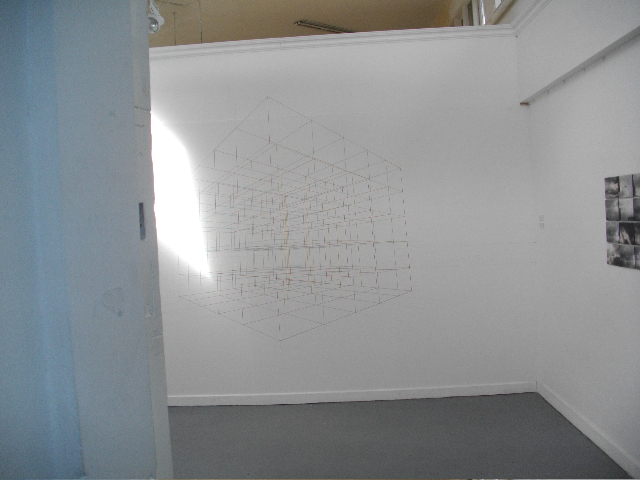

This building and the bank for which it was conceived have become metonyms for the financial disaster as whole, as if the building was both cause and effect, illness and symptom. This crisis has stifled the prospects for a certain kind of architecture, but it is perhaps not a type to be mourned: the golf-club digressions of men gassy on their own importance. And if there isn’t a rush to add to Dublin’s store of new buildings, that doesn’t mean that architecture is dead. With a pen and paper, or just the white wall of a small gallery, it’s entirely possible to work out any orthogonal urges that need expressing. I thought of the unfinished Anglo-Irish building when viewing Anne Cradden’s work in “Edges and Margins,” an exhibition in The Market Studios.

Executed directly onto the wall, this drawing thrills as a powerful piece of op art accomplished with an economy of means. It’s a reminder that our feelings about space can be triggered and affected just through the line on a wall. It’s worth bearing in mind that, at a distance, three-dimensional objects register only as two dimensional, so that Cradden’s drawing of space offers, in effect, a similar experience to viewing the Anglo-Irish building from the opposite side of the River Liffey, as in the following image.

As much as architects need to consider the building as something inhabited by people, it is often the case that a building remains only a spectacle, and often just a two-dimensional one, in people’s lived experience of the city. Consequently, it is sometimes possible to engage with the way in which architecture affects the observer’s consciousness without resorting to the expense of actually building it.

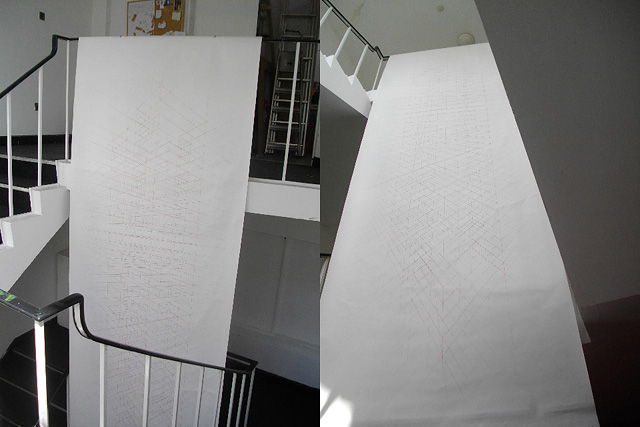

The artist even succeeds interestingly in introducing depth to this work by layering one drawing over another, the bright ink from the background drawing only a little dimmed through the foreground sheet. Another drawing in this show becomes more performatively architectural by occupying a conspicuous spot of the gallery building: A tower of ink lines rises in a stairwell. A modest architectural behemoth that can be rolled up and tucked away in a wardrobe. Imagination and ambition that doesn’t increase our national debt.