Background Flicker

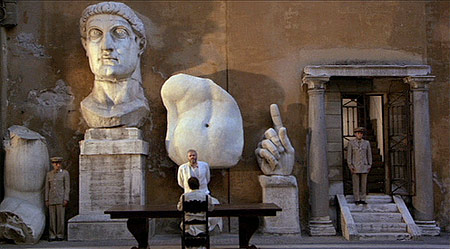

It sounded like a recipe for success: Peter Greenaway as video-jockey, beaming film onto the front of a building with five powerful projectors, and musical accompaniment from Hungarian musician and DJ Yonderboi.

The performance was curated by Collegium Hungaricum, and kicked off the 2nd annual Cinema Total meet. Greenaway started with a rousing speech about the changing nature of cinema, delivered in the type of booming, effortlessly authoritative English accent which should underpin all documentaries, and leaves you feeling thoroughly impressed without really knowing why.

Citing a date in 1983, Greenaway refered to the introduction of infrared TV remote controls into the living rooms of the world; gadgets which allowed us to zap through multiple channels and surf a sea of pictures. The remote control helped usher in the jump-cut era of MTV, and arguably quickened our ability to sort and evaluate visual information, but also shortened our attention spans. Greenaway’s point though, was that this has left us with an innate ability to digest multiple information sources: the past, the present and the future, simultaneously, with only the loosest of narative threads. And this, he insisted, is what people want, and what might shape the cinema of the future.

But what followed was a 60-minute barrage of short film loops, indiscriminately distributed across the screens. Most of the time the same loop was to be seen running simultaneously on one or more neighboring screens, making the five beamers pretty much redundant from a dramatic point of view. Just as there was no interaction between screens, no attempt was made to incorporate the architectural quality of the Collegium Hungaricum building or the surrounding urban space. Night trams, however, occasionally trundled along between the stage and the building, providing occasional but much needed absurd interlude.

The audio coupled to each film loop was fed mercilessly into an echo effect for the entire duration of the set, which might have served to merge one clip into the next, but the result was a cacophony of repeated accoustic phrases as disjointed as the visual onslaught. Far from representing the future, it sounded like an embarrasing throwback to the early days of political sampling in mid 1980s hip-hop or early 1990s industrial music. Every so often a beat would emerge out of the soupy mess, as if to remind us of the enduring relevance of rhythm and syncopation, linearity and digression.

Due to multiple simultaneous communication channels, the typical office worker these days can only expect to enjoy a three-minute burst of concentrated work before the next interruption. In this context, the thought of a new form of cinema, in which plot and dramatic arc are traded for more of the same, seems like a nightmare.