Built in Slumberland

One of my birthday presents this year was the book Architektur wie sie im Buche Steht, which means something along the lines of “Architecture as it is in Books”. This 568-page volume accompanied an exhibition of the same name held in Munich’s Pinakothek between December of last year and March this year.

The book explores the role of imagined architecture in world literature, documenting 120 examples, many of which were visualised in the exhibition in the form of drawings, models and computer simulations. Kafka’s Castle is featued, as are Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo in Akira as well as Thoreau’s wooden hut on Walden Pond.

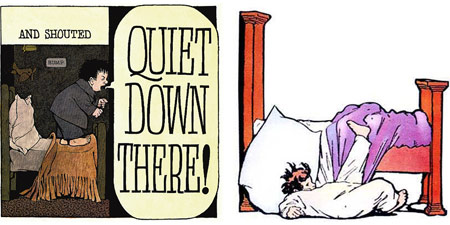

Two nights ago I came across the book’s essay on Windsor McKay’s Little Nemo comic strip, which ran from 1905 in the New York Herald. I’d never heard of it before. Little Nemo explores the dreams of a boy whose nightly adventures revolved around the single aim of reaching Slumberland. Nemo invariably fails in his quest, waking up at a crucial moment in the unfolding drama, having been crushed by giant mushrooms, enslaved or turned into a monkey.

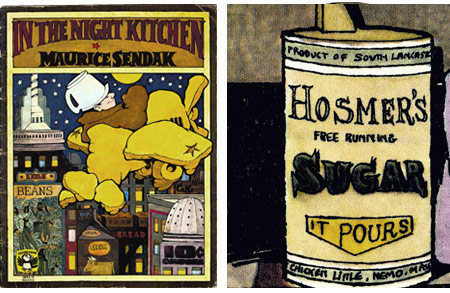

Architektur wie sie im Buche Steht illustrates one of Nemo’s adventures and I was surprised to see that the last panel – showing Nemo standing in his bed – bared more than a passing resemblance to a similar panel from Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen, a story that was a childhood favourite of mine.

Scouring Sendak’s story for clues, I found the detail (below right) on page 12 showing a carton of “Hosmer’s Free Running Sugar”. Around the base of the package are the words “Chicken Little, Nemo Masc ”¦” Remove the comma from the middle and you have, of course, the words “Little Nemo”. The name of Sendak’s protagonist, Mickey, is also surely an expansion of illustrator Windsor McKay’s own surname.

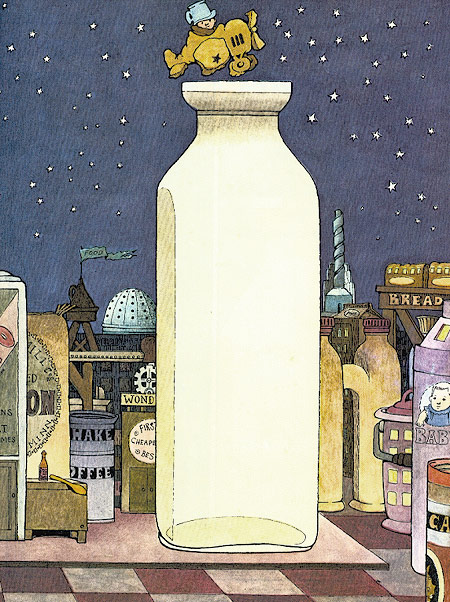

Sendak’s Night Kitchen is a surreal mix of bakery and city. The buildings which form a backdrop to the story are reminicent of 1930s Manhattan skyscrapers but are all made of food packaging or kitchen utensils. Sendak plays with dream-typical effects such as a distorted sense of scale, such as when Mickey takes flight in a small airplane fashioned out of dough and leaps into a giant bottle of milk. At this point too, it becomes clear that the buildings in the background aren’t part of some distant city, but are enlarged freestanding objects within the kitchen itself.

Mickey eventually leaves the Kitchen in the same way as he enters: with a fall. Architecture, or at least, bizzare architectural situations have played a large role in my own more memorable dreams of the last few years. I can’t imagine early exposure to Sendak’s story has anything to do with this, but the role the built environments plays in forming and reflecting the psyche must be one of great important. Maybe I’ll document a few of my own architectural dreams in a future posting…