André Franquin’s Comic Urbanity

I was probably about 12 years old when I first discovered the work of Belgian born artist and writer André Franquin whilst on a family holiday in France. One afternoon I stumbled upon an annual of his wonderfully gaga series of Gaston comics in the house of a family friend.

Protagonist Gaston Lagaffe (French for ‘the blunder’), is a pathalogicaly lazy and accident prone office boy working in the fictionalised setting of the comic’s own publishers. When the first strip appeared in 1957, Franquin was already well known for his work in the comic magazine Le Journal de Spirou. Gaston was to become his most famous work, which he continued until his death 40 years later.

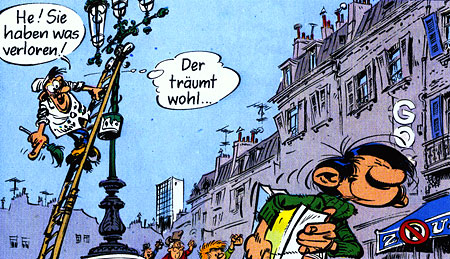

Although I understood nothing of the text, I was immediately fascinated by Franquin’s super-detailed style of drawing: an almost obsessive density of visual infomation was packed into each panel with an eye for detail that made the reading of the texts only a secondary concern. I could spend hours losing myself in the lines of a background roof-scape, or wondering about the arrangement of rooms in the pen-and-ink virtuality of the office, a kind of omnipresent meta-character.

Looking at the comics now, I have a feeling they’ve played a role in shaping my own perception of European city architecture, especially Paris. Many Gaston stories feature street scenes of tumble-down, late 18th Century buildings: all shuttered windows, steep roofs and crooked chimney pots. These are occasionaly juxtaposed by 1970s office blocks and are invariably decked out with the chaotic contemporary patina of commercial signage, nonsense trade names, neon lights, TV aerials and telephone wires.

It was Franquin’s skill as a caricaturist which enabled him to distill so many features of urban life into vibrant drawn replicas which feel right without strictly having been drawn ‘right’. Franquin’s style was technical but never cold. Pen strokes often taper to a hair-line and are left unjoined in expressive gestures. This, combined with an intuitive feel for lighting, both natural and artificial, imbue his work with an organic warmth.

Memorably in one episode, Gaston and friend take a rubber ball and two wooden paddles out onto the street for an anarchic game of city-wide racquetball. The little red ball dissapears down busy city thoroughfairs and alleyways causing havock. Of course, it bounces back some time later for the magical return volley, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. To my pre-teen mind, the thought was mind-boggling and exhilarating. Despite the rain soaked streets, grumbling old men and the heavy traffic, Gaston’s home town was city I wanted to live in.

All images taken from the German edition “Gesammelte Katastrophen, Band 11”, Carlsen Comics, 1994